I walked through the Phil and Ginny Leach Wildlife Sanctuary as my eyes strained at the sun-rays bouncing off the white blanket of snow. I took the time while out there to remember my previous experiences. Many of my fondest memories have been while out in areas just like this. One of the most important parts of conservation work is understanding the interactions between plants and animals in the area that you are working in. A term that I was introduced to during my experience at Maine

Species account on a Downy Woodpecker.

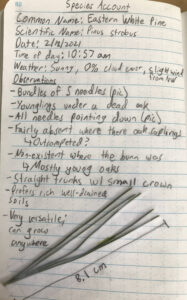

Species account on Eastern White Pine trees.

Coast Semester at Chewonki in Wiscasset, Maine was being a naturalist. This term reemerged throughout the many future endeavors that I went on. As a 17-year-old, I did not fully embrace this idea or understand what it meant. I would get glimpses into the understanding of it when I was told to count the number of birds that visit a bird feeder in an hour time slot each week. Why am I doing this? Or learning the identification of the native tree species that live on the Maine Coast along with their common and scientific name. What is the point of this? Or trekking through the woods in search of vernal pools to locate and mark them for future evaluation of their health. Where are we going? Or spending one day each week going to new sites like beaches or mountaintops where we learned about how the features were formed, and what plant and animal species live in the area. We do this every week?! Or writing species accounts on various plants and animals. I have to write another one? Or spending two nights and three days alone in the woods with no one but myself. Am I sleeping out here alone? Or simply sitting in the forests and watching it exist as it has for thousands of years. Why am I just sitting here? As a 17-year-old, I was not yet able to appreciate what I was learning during all these experiences.

A moose sighting on a canoe trip in 2013 in northern Ontario.

I continued on with my life with this new idea in my head about being a naturalist. I carried it with me as I spent my summers up in northern Ontario where I canoed on some of the most remote areas that I have ever been to. Animal sightings of bald and golden eagles, moose, and herons were all too common during our trip. Wolf, bear and even wolverine sightings were less frequent but did occur. On one special day, we stumbled upon the aftermath of a wolf feast on a deer. This was a stark reminder of the territory that we were traveling through. My appreciation for the natural world was growing at a rapid pace, and the idea of being a naturalist started to come into focus. I began to realize what my mistake was with my past experiences with the natural world: I was putting myself at the center focus. My inner dialogue consisted of this: Why am I here? What I am doing? Where are we going? The questions that I should have been asking needed to be less self-centered and much more thoughtful. Questions like: Why are vernal pools so important? What animals rely on these pools? Why do animals prefer a certain habitat over another one? What animals rely on one another for survival? These questions are at the heart of being a naturalist.

A very rare wolverine sighting in northern Ontario!

Ultimately, these questions are a skill. A skill that we as humans must learn and use in order to save our planet, and that skill is called listening. I finally understand why I had simply just sat in the woods and heard the sounds of nature. I was listening to nature! If we want to be successful conservationists, then we have to be naturalists. We must listen to the ecosystems and understand what their needs are. Similar to the silliness of putting a road somewhere where there are no cars, it is just as silly to protect an area without first listening to its needs. We all have a lot of work to do in the coming years to help our planet heal, but one thing that we all can do right now is start listening to what nature has been telling us.

Downy woodpecker spotted on the Leach property.